The following excerpt is from a much longer article by Steven C Smyrl, published in the January 3, 2011 edition of IrishTimes.com . If you have Irish ancestry, the article is a must-read…

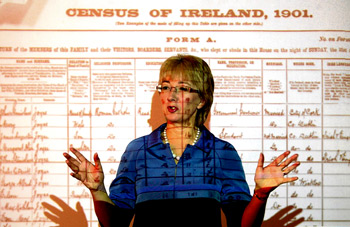

GIVEN the astounding success of the National Archives’ free online database to the 1901 and 1911 census returns, the potential for roots tourism currently locked away in the 1926 census is incalculable.

When it comes to preservation of the written record, Ireland’s reputation is poor. For a literary nation priding itself on such manuscript gems as the Book of Kells and the Annals of the Four Masters, we should be appalled that our reputation internationally is one of a nation without records. It is difficult to argue against such a view when over the centuries through ignorance and carelessness we have destroyed and discarded the sources for the history of this island. Until the Victorians sensibly provided Ireland with a Public Record Office in Dublin’s Four Courts complex in 1867 the records of parliament, government and courts were constantly in a state of flux, being brought from one temporary location to another. In this new repository records dating back as far as the 12th century were conserved and catalogued. Its holdings included parish registers, wills, census records, court files, and a whole array of records, minutes and files of government administration.

Imagine then the horror when in 1922, in an orgy of destructive violence, the combatants in the civil war brought about the virtual annihilation of the largest body of material on the history of this island ever gathered together. At this stage it hardly matters whose fault it was: the fact that it occurred at all is shame enough. In one catastrophic act of stupidity the people of Ireland were forever robbed of almost all of their national memory.

In the decades since 1922 Irish academics and genealogists have become adept at squeezing every last bit of information from the surviving records. We have learnt to recognise the value of secondary sources, of transcripts and abstracts and even surviving indexes to otherwise destroyed records. However, nothing has had a more immediate impact upon the value of Irish records than the new technologies which have been rolled out over the past decade. Sources of information once impenetrable are now easily and readily accessible. The most pertinent example of this is the online 1901 and 1911 census database created by the National Archives (the successor body to the Public Record Office of Ireland). Until these two sets of census records (which are complete, island-wide) were digitised and indexed, access was limited to knowing approximately where a family resided. Now, at the press of a button, one can establish how many butchers lived in Athlone in 1911 (18), the number of Jewish people residing in Cork city in 1901 (401) or even if anyone recorded in the 1901 census was born in Serbia (one).

Search the 1901 or 1911 Irish Census at the National Archives of Ireland website.

Pingback: Genealogy Newsline Vol. 1 # 1