The following article was written by my friend, William Dollarhide:

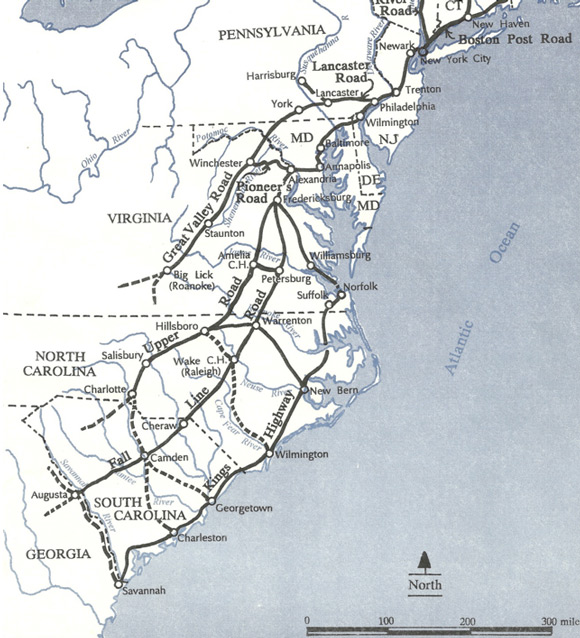

Note: Any old wagon roads identified here in bold type are shown graphically on the map below.

If you had ancestors who went from the Chesapeake to the interior of North Carolina in the middle 1700s; or if you had ancestors who arrived in America during the 18th century and immediately headed for the western area of North Carolina now known as Tennessee; then you may like to know how they got there.

The first farming communities in the interior of North Carolina were established by a group of people who came from the tidewater area of Maryland and Virginia. They brought with them a good understanding of how to raise tobacco, the chief crop of the tidewater region of the Chesapeake, which became a primary crop of North Carolina. Many of these people were second and third generation Chesapeake residents, but a sizeable number of them were newcomers to America, a group of people who are often called the Scots-Irish.

Crossing the Blue Ridge Mountains

Before 1746, travelers from the Chesapeake into western Virginia were compelled to first go north to Philadelphia, then west on the Lancaster Road, then southwest on the old Philadelphia Road through York, on to the Potomac River, and connecting with the Shenandoah River Valley. A key historical event which influenced the migration of people from the Chesapeake to points west and southwest was the opening of the first wagon road across the Blue Ridge Mountains in 1746. It became known as the Pioneer’s Road, and allowed for wagon traffic from Alexandria to Winchester, the westernmost town in Virginia at that time. Winchester was located on the Great Valley Road. By traveling from Alexandria overland to Winchester, the route to access the Great Valley Road had been shortened dramatically. The trace today of the Pioneer’s Road is very close to that of the modern U.S. Hwy 50, which crosses the Blue Ridge Mountains via Ashley’s Gap.

As a result of the opening of the Pioneer’s Road, thousands of Scots-Irish immigrants to America changed their travel plans after hearing from relatives in America. Before 1746, the primary port of entry to the American colonies was Philadelphia. After 1746, Alexandria, Virginia on the Potomac River became an important port of entry for the newcomers coming from the Irish Sea.

Who were the Scots-Irish?

“Scots-Irish” was a name given to the people who came to America from about 1717 to 1775 by way of northern Ireland, or Irish Sea ports on either side of the border of Scotland and England. Border clan people had first gone to northern Ireland beginning about 1603-1610, the first few years of the reign of James I, the first monarch to rule both Scotland and England. Soon after an English take-over of the Province of Ulster, and with the support of King James I, thousands of border clan people were encouraged to leave their traditional clan homes along the English-Scottish border and take up tenant farms in northern Ireland. The inducement was a parcel of tenant land, which the borderers could have as their own for a lease period of 100 years. Over the next century, the system worked reasonably well. Working on tenant farms as share-croppers, the border clan people established thriving flax fields in northern Ireland, and built a linen trade that was the envy of Europe.

Although many lived in Ireland for decades, these folks did not think of themselves as Irish, and if asked would probably say something like, “We’re no Eerish bot Scoatch.” In fact, most of the clans of the borderlands considered themselves Scottish rather than English, whether their traditional lands were on the English side or the Scottish side — they had a history of taking whatever land they wanted and were famous for their centuries of fighting Scottish kings, English kings, or each other — it really didn’t matter.

Another big change in the lives of the border clan people took place in 1707 with the official unification of Scotland and England into the United Kingdom of Great Britain (UK). The border clans became intolerably resistant to the English, who were attempting to combine the small crop farms along the border into more profitable sheep ranches. The Scottish Thanes were replaced with English landlords, mostly absentee landowners living in London. As a result, thousands of borderers were faced with seizures of land, and removals to Northern Ireland. This time, the clan people were not given very good treatment, with higher rents and shorter leases, and as earlier leases ran out, the tenants were replaced with new border clan people at higher rents. Beginning in about 1710, terrible droughts, famine, and the collapse of the linen trade in Northern Ireland put the clan people into dire straits, and living there became nearly impossible.

By 1717, dispossessed Scots-Irish began moving to America, and over the next 50 years or so, it is estimated that over 275,000 of them went to the American colonies. Most of them found themselves traveling into the wilderness of colonial America, mainly the Appalachian region, stretching from western Pennsylvania to Georgia. Almost exclusively Scots-Irish immigrants settled these areas. In keeping with the Scots-Irish desire to leave the populated areas of America and head into the wilderness areas, it was these folks who created a demand for new wagon roads.

Roads to Tennessee and North Carolina

As early as 1740, the Shenandoah Valley was the route of The Great Valley Road of Virginia, which continued as a wagon road as far as Big Springs, Virginia (now Roanoke). During the middle of the 1700s, the route was often called “The Irish Road,” because most of the travelers were Scots-Irish immigrants. Today, the trace of the Great Valley Road is nearly the same line as U.S. Highway 11 (or I-81). In 1746, travelers on the Great Valley Road at Big Springs had to leave their wagons and use pack horses to continue, either due south into central North Carolina, or continue into the valleys of the Clinch, Powell, or Holston Rivers leading into western North Carolina, now Tennessee.

But in just a few years after the opening of the Pioneer’s Road in 1746, the Upper Road became a wagon route as well. The Upper Road took off from the Fall Line Road (which is the same as U.S. Hwy 1 today) at Fredericksburg, Virginia, and paralleled the Fall Line through Virginia, but reached North Carolina some 60-70 miles west of the Fall Line Road. A look at a modern road atlas of North Carolina shows the main population centers along Interstate 40 as Raleigh, Durham, Burlington, Greensboro, and Winston-Salem – all communities that were first settled as a result of the Great Valley Road or the Upper road (The Upper Road is the only colonial wagon road that does not exist today as a modern highway – it crossed several streams and rivers that are now large man-made lakes). Virtually the entire Piedmont region of North and South Carolina was settled via the Great Valley Road during the latter half of the 1700s.

The first land grants in north central North Carolina were in 1746, coinciding with the advent of a wagon route (the Pioneer’s Road) that became possible in the same year. Before that date, land sales in North Carolina were limited to the coastal areas and up a few rivers. The interior land grants came as a result of Lord Granville, the proprietary governor, who opened the northern tier of North Carolina’s modern counties for sale in that year. The area became known as the “Granville District,” which attracted thousands of migrants from the north, particularly people coming via the Chesapeake region of Virginia and Maryland.

Some traffic came from eastern North Carolina into the western regions, but the first wagon roads came from the north. For example, many Quakers who had settled around Albemarle Sound before 1700 were to head west into the interior of North Carolina, but were later than the first wave of immigrants coming down from the Chesapeake, e.g., Quaker communities in Randolph, Caswell, and Orange counties, did not begin until the early 1770s.

Follow the Markers

Dollarhide’s Genealogy Rule No. 17: Finding the place a person lived may lead to finding that person’s arrest record.

As a genealogist, understanding the migration routes my ancestors followed has helped me find markers they dropped along the way. Since most of the colonial wagon roads can now be identified on modern maps as county, state, U.S. or Interstate highways, it is possible to draw a line through the modern counties through which the old routes passed. That makes for a research list of counties where records can be searched – and I have found evidence of my ancestors in counties I never would have thought to look otherwise. The most useful records have been land and tax records, which confirm that a person lived in a certain place at a certain time. Land records are more complete than virtually any other genealogical source record and are easier and quicker to use than other record types. They act as my place finder in determining where a particular surname may be located. Often, it is an understanding of the wagon roads they took that will lead us to the right county where the records still exist.

But, in addition, an understanding of the routes will lead a genealogist to the location of regional record repositories. For example, the McClung Collection at the Knox Public Library in Knoxville, Tennessee is a gold mine of information about people coming down the Great Valley Road into eastern Tennessee. Other great repositories are located at Bristol Public Library, Bristol, VA; Roanoke Public Library in Roanoke, VA; Jones Memorial Library in Lynchburg, VA; and the Handley Regional Library in Winchester, VA. These are specialized collections in which migrations along the Great Valley Road can be found. And, of course, the collections at the Library of Virginia and Virginia Historical Society in Richmond are outstanding, as are the collections at the Maryland Hall of Records in Annapolis.

So, get on board the Great Valley Road — it may be the clue to where your ancestor left markers for you to find.

For further reading , see:

- Map Guide to American Migration Routes, 1735-1815, by William Dollarhide

- British Origins of American Colonists, 1629-1775, by William Dollarhide.

Picked up after 5 yr layoff with ancestry stuff, extensive research. Family had settled mid 1700’s in Montgomery Co Virginia in Appalachians. Shortcut description “dirt poor Appalachian hill people” with name of Aul, All, Alls, and perhaps others (perhaps Ahl?)

Learned that many name spellings are not chosen, but misinterpreted (or just assigned by nothing more than misinterpretation – example military requires to state name, but you must state name to get paid), even if in reality can’t read and write – not meant to degrade, just a fact. Anyway, I was impressed with your knowledge and approach, would like value advice. This family still has not determined the location of their origin, how they may have lived, abroad. Can you point me in the right direction? Thank you.