The following article was written by my good friend, William Dollarhide. Enjoy…

Dollarhide’s Genealogy Rule No. 9: An 1850 census record showing all twelve children in a family proves only that your ancestors did not have access to birth control.

The National Archives’ Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives (Washington: NARA, 1982), p.21, states: “The (1790) schedules for Delaware, Georgia, Kentucky, New Jersey, Tennessee, and Virginia were burned during the War of 1812.”

That statement is not correct.

First of all, there was no federal census taken in Tennessee in 1790, which did not become a state until 1796. Tennessee was formed from the old Southwest Territory, which, along with the Northwest Territory, was specifically left out of the federal census taken in 1790. (See note 8 below). As to the others, when the British Army burned Washington in 1814, there were no original census schedules from the states located there. All of the original manuscripts were still located in the offices of the clerks of the federal district courts for each of the various states. There were no copies made, and none of the original censuses were ever sent to Washington until after an 1830 law required that they be transferred to the office of the Secretary of State. As a result, the only census schedules whose destruction could be blamed on the British Army was the 1810 census schedules for the District of Columbia, whose District/Supreme Court was located in Washington, DC.

If Not the British, Who Gets the Blame?

All of the early census losses, particularly those from 1790 through 1820, were a result of mishandling or neglect by the clerks of the federal district courts. Since the first census law (an act passed by Congress on 1 March 1790, published in United States Statutes at Large, Volume 2, page 564), the U.S. marshals were responsible for taking the census. In 1790, there was one U.S. marshal for each state/district, plus Kentucky (a district of Virginia) and Maine (a district of Massachusetts). The marshals appointed assistants to take the door-to-door enumeration in divisions to consist, as the 1790 act put it, “. . . of one or more counties, cities, towns, townships, hundreds, or water courses, mountains, or public roads.”

The 1790 census act gave enumerators nine months from the census day (the first Monday in August 1790) to enumerate the people, to post copies of the statistics “at two of the most public places” in the divisions, and to send the name lists to the marshal. The marshal then had four months to send “the aggregate amount” of each census to the president, having deposited the actual name lists with the clerk of the federal district court. Although the law was clear that the clerks were directed to “receive and carefully preserve the same,” some of the clerks obviously failed in their duties, particular those clerks in 1790 for the states/districts of Georgia, Kentucky, New Jersey, and Virginia. In 1800, blame the clerks for the territories/districts of Illinois, Indiana, Mississippi, and Missouri. In 1810, blame the clerks for the Michigan, and Ohio, and possibly the District of Columbia (along with the British); and in 1820, blame the clerks for Alabama and Arkansas.

In an act of 28 May 1830 (U.S. Statutes at Large, Vol. 4, p. 430) the clerks of the district courts were ordered to transfer to Washington all of the original census name lists in their care (those of the 1790 through 1820 censuses). The census losses, 1790-1820, are the only statewide census losses, except the 1890 census, lost resulting from a fire in 1921. There were missing counties, missing towns, missing E.D.s for censuses after 1820, but there were no other state-wide losses. The reason for the early census losses lies in the way the original censuses were treated by the clerks of the federal district courts. The British Army had nothing to do with it.

Now, if an official publication of the keeper of the original census manuscripts (the National Archives) dispenses incorrect information about the losses of the earliest censuses, the possible result is that people tend to believe them, and then the misinformation is repeated by other agencies. For example, at the website for the Georgia State Archives (ADAH), the devastating loss of Georgia’s 1790, 1800, and 1810 federal censuses was explained as “probably lost when the British burned Washington in 1814.” If Georgia genealogists were to do a little research in the federal district courts of Georgia, they might learn that the 1790 census schedules were first deposited at the office of the clerk of the district court within Georgia’s first U.S. District Court House, still located in Savannah, Georgia. There may have been multiple court buildings there since 1790. But the question arises: has anyone ever gone down to the second basement or third attic in the present court building looking for boxes of paper, bound volumes, loose manuscripts or any other evidence of lost census schedules? Probably not – after all, if the British burned them in 1814, why look?

A repeat of the district court house search exercise should be done in any state with one or more lost census years, 1790-1820. (They are listed in the table below). A place to start is any Historical Records Survey documents that included the federal district courthouses for those states – these were the WPA projects done in the late 1930s and early 1940s to conduct inventories of historical documents found in county, state, or federal court houses. Projects were done in all states, but few of the projects ever reached publication, and the work ended with the onset of World War II. Many of the field notes and unpublished inventories ended up in the National Archives.

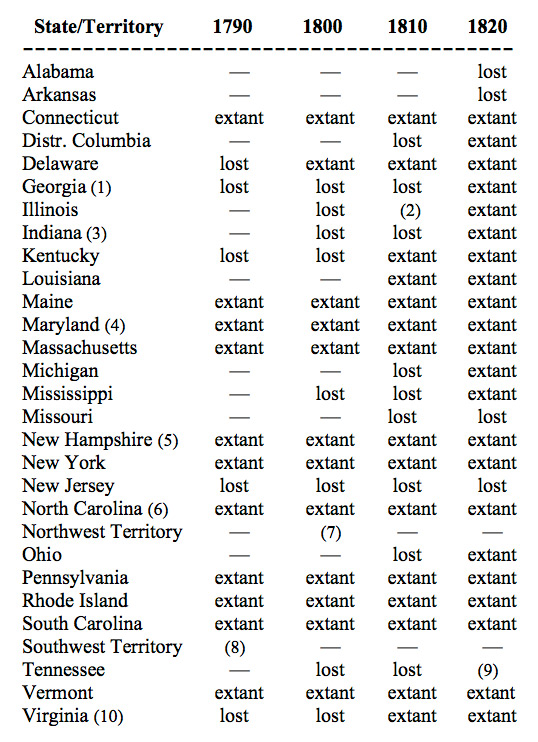

Statewide Census Losses, 1790-1820

The table below shows the extent of statewide census losses for the 1790 through 1820 censuses.

A dash (—) in a column means a census was not taken for that state in that year. “Lost” means the census returns for that state were not sent to Washington after an 1830 law required their return, and were probably lost prior to 1830. “Extant” means the manuscripts of the census returns survive and microfilm/electronic copies of them are available.

Notes:

(1) Three counties are missing from the 1820 Georgia schedules.

(2) Of Illinois Territory’s two counties in 1810, Randolph is extant and St. Clair is lost.

(3) Missing from the Indiana 1820 schedules is Daviess County.

(4) Three counties are missing from the Maryland 1790 schedules.

(5) Missing from the 1790 New Hampshire schedules are thirteen towns in Rockingham County and eleven towns in Strafford County.

(6) Missing from the North Carolina schedules are three counties in 1790, four counties in 1810, and six counties in 1820.

(7) In 1800, about a fourth of the population of the Northwest Territory was in Washington County, whose original census name list was discovered among the papers of the New Ohio Company in Marietta, Ohio. All other counties were lost.

(8) In a 1790 letter to Southwest Territory’s Governor William Blount, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson asked the Governor if he could have all county sheriffs take a census there, even though the first census law did not include territories, and Jefferson could provide no money for the effort. Governor Blount complied, but with a tally of the inhabitants only. Six years later, the Southwest Territory became the state of Tennessee.

(9) In 1820, two federal court districts were in place in Tennessee, one with an U.S. Courthouse in Nashville, the other in Knoxville. The original censuses returned to Washington according to the 1830 law were from the Nashville district only, representing the western two-thirds of the state. The twenty eastern counties enumerated within the 1820 Federal Court District out of Knoxville were not received in Washington and are presumed lost.

(10) The Census Bureau’s printed “Heads of Families” index to the 1790 census includes Virginia. However, these names were extracted and compiled from county tax lists of Virginia 1787-1789. Virginia’s original census schedules for 1790 were lost.

(11) An earlier version of this table was published in The Census Book: A Genealogist’s Guide to Federal Census Facts, Schedules, and Indexes, by William Dollarhide.

Excellent article.

When I was living in Arlington, able to “live” at the National Archives, I was amazed at how frequently misinformation was dispensed by staff members to the public, such as Union (Civil War) muster and pay rolls contained no “genealogical” information–many have an age, place of birth, name of a parent or other relative and even a physical description, all of interest to the genealogists I know, and especially the latter because there are few other places you likely to find someone’s physical description.

That said, the “1790 Census of Virginia” issued by the Census Bureau is NOT a collection of tax records, but of individual county censuses taken largely between 1783 and 1785, with some later year, the city of Richmond being included among the later and also being every name! There are two additional “substitutes” for the 1790 census, one being Virginia Taxpayers 1782-1785, by Augusta Fothergill and Nettie Schreiner-Yantis’ 1787 Census of Virginia which is also a collection of personal property tax rolls. That year is significant because it is the only year in which the taxes identified persons other than the head of household by name STATEWIDE, though those so named were only males of the age of 16 or older.

John Frederick Dorman serialized in his magazine Virginia Genealogist abstracts of the personal property taxes for the year 1800, but with that journal ceasing publication with Volume 50, it is not complete.

Finally, there are 16 counties missing from the 1810 census of Virgina. Personal property taxes for those counties have been published as “Substitute for the 1810 Census of Virginia”.

In your speaking of census pages, etc., being missing, on multiple occasions I have encountered microfilm where a page appeared to be blank, but having access to the actual census books at the National Archives, I found there was no only writing on the page, but that it was quite legible, even “crisp”.

How could that be possible?

Well, early microfilming technology had no appreciation of the fact that a black & white camera can “see” only” BLACK or WHITE. All other colors are reduced to shades of gray and if light or dark enough, become indistinguishable from the true black or true white. The problem could have been eliminated in many instances if the camera operator had simply used a filtering lens. That is why it is wise to use a sheet of pastel paper or plastic to “focus” blurred or indistinct microfilmed images, with amber seeming to do the best job.

The advent of scanners, as they “see” in “True Color”, has eliminated much of this problem in the images that are being “added” to the internet, but noting the wide differences in image quality between Ancestry and Heritage Quest, among others posting census images, though I do not know this for a fact, I cannot help but think the Ancestry images were taken from the original microfilm and the Heritage Quest images from that actual books.

Michael, thanks for adding some great details about the early Virgiinia census substitutes. Re your comment about the difference between early Ancestry vs Heritage Quest scanned images . . . both Leland and I were at HQ (from the early 1990s) during the ten years or so that HQ pioneered census scanning technology using “gray-scale” imaging rather than “black and white” imaging done by Ancestry. -bill$hide

On the single roll of this microfilm

publication, M1803, is reproduced population

census schedules for Washington County, Ohio,

from the third census of the United States,

taken in 1810.

The 1810 population census schedules

received by the National Archives from the

Bureau of the Census include none for the

State of Ohio. In 1961, the schedules

included on this roll of microfilm were in

the Marietta College Library, Marietta, Ohio.

That year, through the courtesy of the

Library, they were loaned to the National

Archives for microfilming. At that time,

the negative microfilm was turned over to

the Marietta College Library, while the

positive was placed in the Microfilm

Reading Room of the National Archives,

Washington, DC.

This positive copy was assigned the number

GR3, by which it was referred to in the “Guide

to Genealogical Research in the National

Archives” (National Archives and Records

Administration, revised 1985). In 1994, GR3

was assigned a new number, M1803, in order to

issue it as an official National Archives

Microfilm Publication.

The census schedules on this roll were

contained in one bound manuscript volume that

was unpaginated. The arrangement of the

schedules is alphabetical by name of township.

Thanks, Ernie. The table needs to updated to show a note (7) under the 1810 column for Ohio. How I missed this, I don’t know. I guess it was the extend of my knowledge when the Map Guide book was first published in 1987. I have since learned about Rufas Putnam’s New Ohio Company records that ended up at the Marrietta College Library, and I should have noted that they included the original census schedules for Washington County 1810. -bill$hide

The 1820 US census for New Hampshire is missing all of Grafton County. I recollect that there are towns in other counties missing too, but this requires substantiation. I have checked in NH, the National Archives District Office in Waltham MA and online resources and none have Grafton County or were aware that it was missing. It would be very helpful to researchers to get this information out. I can’t tell you how many years of search were lost due to the absence of this knowledge, even to the staff in Concord NH archives and library.

Thanks Judith, The National Archives has no where confirmed that Grafton County NH 1820 is missing — but I believe you. Hopefully, readers of this “Early U.S. Census Losses” article will read all of these comments as well — and I thank you for adding this valuable information. -bill$hide

Pingback: Ask DGS - 1790 Census for Delaware - Delaware FamiliesDelaware Families

I approved the Ask DGS comment, even though the correct answer was already covered in paragraph one of this article. After the 1790 enumeration, all 1790 originals were supposed to be held and maintained at the office of the clerk of U.S. Circuit Court for each state. A federal law in 1830 asked for the return of the originals to Washington DC, and some of the states could not comply. Don’t blame the British for burning something in 1814 that was never there yet.

Pingback: Researching Your War of 1812 Ancestors Online - Heart of the Family™