The following timeline is excerpted from William Dollarhide’s new book, California Name Lists, 1700 – 2011, with a selection of National Name Lists, 1600s – Present.

For genealogical research in California, the following timeline of events should help any genealogist understand the area with an historical and genealogical point of view:

1535-1542 Spanish Claims. The first European visitors to the Pacific coast of North America were convinced that California was really an island. In 1535, Hernando Cortes was the first to see California, and in 1539, Francisco de Uloa explored the gulf of California. The first claim came in 1542 when explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo anchored his ship in San Diego Bay and claimed the entire “island” for Spain, which he named California. One explanation for the name was that Cabrillo had been reading Ordoez de Montalvo’s romance of chivalry, Las Sergas de Esplandian (Madrid, 1510), in which is told of black Amazons ruling an island of the name California near the Indies. No one can find any other reference to the name California before 1542, and it has no other known Spanish origin.

1579 British Claim. Never one to cede anything to the Spanish, Sir Francis Drake sailed up the Pacific Coast beyond San Francisco Bay and claimed the entire region for England, naming the area New Albion. But the British claim was never reinforced by colonization.

1602 Spanish Claims Confirmed. Sebastian VizcaNíno charted the Pacific Coast and confirmed Spain’s claim to the region, from the southern tip of present Baja California, Mexico to the northern tip of present Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

1603-1768. Spanish Presidios Established. For the next 165 years, Baja (lower) California and Alta (upper) California were part of New Spain, which was a description of all Spanish claims in the New World. During this time, California was mostly ignored by Europeans, except as a re-supply point for Spanish ships sailing from Manila and other Pacific outposts before returning to Spain. During the late 1600s a few presidios (forts) were established as protection for the re-supply ports, such as the presidios at Monterey Bay and San Diego Bay. The Spanish were reacting to the intrusion of Russian and British trading posts established just north of San Francisco Bay, but both intruders left California after only a few years.

1769-1820 Spanish Colonial Era. The Spanish colonization of California did not really begin until the arrival of Junipero Serra in 1769. Serra was the Franciscan monk who founded the first nine California missions, ranging from San Diego Bay to San Francisco Bay. The Spanish were to establish a total of 21 missions, all connected with a wagon road called the El Camino Real (the Royal Road). For the most part, the Spanish missions were successful in converting the local Indians to Roman Catholicism, but a few California Indian tribes resisted by attacking and burning the missions. In response, the Spanish government provided military protection for the missions by establishing several more presidios, evenly distributed between the coastal missions. During the Spanish era, over 100 presidios were established. Spanish pueblos (communal villages) were the first civilian towns in California. Mission workers were provided by the Catholic Church, while the presidios were manned by Spanish soldiers. But to provide civilian farmers and workers for the pueblos, incentives were required to get people to move there, and thus, a system of land grants, tax breaks, and other incentives was established. To attract settlers to the new towns, the Spanish government provided free land, livestock, farming equipment, and an annual allowance for the purchase of clothing and other supplies. In addition, the settlers were exempt from all taxes for five years. In return for this aid, the settlers were required to sell their surplus agricultural products to the presidios. The Spanish created three pueblos in California, the first was San José, founded in 1777. It was followed in 1781 with El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Angeles (the Town of Our Lady Queen of the Angels). By 1790, the Los Angeles pueblo had 28 households and a population of 139. By 1800 Los Angeles had 70 households and a population of 315. The villa de Branciforte near present Santa Cruz was another pueblo established in 1797, developed primarily as a place for discharged soldiers from the presidios, but the Branciforte pueblo was never able to attract many soldiers and was abandoned in 1802. The San José and Los Angeles pueblos were still active when California became an American possession in 1848.

1819 Adams-Onis Treaty. The treaty’s initial agreement involved Spain’s cession of Florida to the U.S., but also set the boundary between the U.S. and Spanish Mexico, from Louisiana to the Oregon Country. In this treaty, the line between the Oregon Country and Spanish California was set as the 42nd parallel, where it remains today. The treaty was named after John Quincy Adams, U.S. Secretary of State, and Luis de Onis, the Spanish Foreign Minister, the parties who signed the treaty at Washington on February 22, 1819. John Quincy Adams was given credit for a brilliant piece of diplomacy by adding the western boundary settlements with Spain to the Florida Purchase. It was considered his crowning achievement, before, during, or after his presidency.

1821-1848 Mexican Era. Colonial Spanish rule in California ended when Mexico gained independence from Spain in February 1821, but the Californios never heard about it until the new Mexican governor arrived in November 1822. At first, the transition of power had no change to the California way of life. But within just a few years, the mission system in California came to an end. As early as 1826, Americans began visiting California after establishing overland routes from the Rocky Mountains. After some initial resistance, the Californios accepted their intrusion into the area. As the most northern and western province of Mexico, California had few manufactured goods, and the Americans were welcomed for the items they brought for trade. By the early 1830s, the mission communities established by the Spanish were absorbed into the Mexican civilian government. The mission properties were distributed to soldiers in lieu of wages and to Mexican citizens in return for political favors. The local natives who remained were assimilated into the local society serving as laborers, household servants and vaqueros (cowboys). The Mexican government did create more pueblos, mostly from converted missions (such as those in Sonoma and San Diego). But mainly, Mexico concentrated on the land grant process which the Spanish had initiated. With the demise of the Mission system, California evolved into an isolated province dominated by a series of large ranchos, some as large as 100,000 acres in size. By 1840, huge cattle ranches stretched from San Diego Bay to San Francisco Bay, including the great Central Valley of California.

1840s Manifest Destiny. In 1841, the first wagon train left Missouri for California, even though the area was not part of the United States, and the settlers had no guarantee they would be able to stay. During the 1840s, the American government was under the influence of an unofficial but practiced policy called “manifest destiny,” meaning the U.S. believed they had the God-given right to take the entire continent by any means.

1845 Texas Annexation. Clearly, Americans began to covet the area of the southwest, and in fact, many historians feel that the annexation of Texas in 1845 led to a war that was as much to capture California and New Mexico from Mexico as it was to take the Rio Grande valley. After the 1845 annexation of Texas, the U.S. honored the Republic of Texas claim to the Rio Grande valley. This claim was the basis for the Mexican-American War, which began in December 1845 when U.S. forces invaded the Rio Grande valley and took possession of the area.

1846 Oregon Country. Since a treaty in 1818, the U.S. and Britain had agreed to joint occupancy of the Oregon Country, defined loosely as running from the Boundary (Siskiyou) Mountains of California to the Russian America boundary at about the 54th parallel and from the Pacific Ocean to the Continental Divide. In 1819, the Adams-Onis Treaty set the Oregon boundary with California as the 42nd parallel. Finally, in 1846, the U.S. settled with Britain its long-held claim to the Oregon Country, establishing the 49th parallel as the northern boundary with British territory, and confirming the southern boundary of Oregon with California as the 42nd parallel.

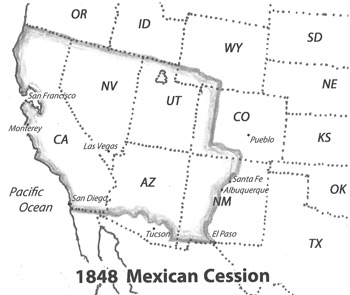

1848 Mexican Cession. In 1848, as part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ending the war with Mexico, the U.S. officially acquired the Rio Grande area by conquest, the portion which extended upriver through present-day New Mexico and into Colorado. In satisfaction of its “manifest destiny” urges, the U.S. also acquired from Mexico the cession of California and New Mexico, which included present Colorado (west of the continental divide), and all of the present states of Utah, Nevada, and California. As compensation for the Mexican Cession, the U.S. paid Mexico 18 million dollars for an area that was comparable in size to the Louisiana Purchase, and was over half of the Republic of Mexico. With the addition of the Oregon Country in 1846, and areas acquired from Mexico in 1848, the United States, for the first time, was a nation from “sea to shining sea,” a goal of American expansionists dating back to George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. “Manifest destiny” was no longer a goal, it was a reality.

1849-1860 Gold Rush, Statehood, and Population Surge. Immediately after becoming an American possession in May 1848, California was to rapidly expand, in fact the dramatic expansion was more than anyone could have foretold. The reason for California’s sudden rise, of course, was that gold was discovered, creating a stampede of prospectors from all over North America. In just a few months, the population in California went from less than 2,000 Americans in December 1848 to nearly 93,000 (counted in the June 1850 federal census). California was never a territory, and after the State Constitutional Convention convened in Monterey in late 1849 and early 1850, Congress declared California a state on 9 September 1850. Statehood led to the establishment of a state government that rapidly organized the entire state into counties, taxing districts, and voting precincts – units of government that quickly began creating name lists of its constituents. By 1852, a total of 260,949 people had come to California, per the state census of that year. And by 1860, just ten years after becoming a state, nearly 380,000 people had come to California.

While the gold fields of Northern California and the first transcontinental railroad in 1869 contributed heavily to the growth of the state through the latter half of the 19th Century, the growth of Southern California in the early 20th Century was even greater. One explanation came from Buckminster Fuller, who observed that “the entire continent is tilted and everything loose slides into Southern California.”

See: California Name Lists, 1700 – 2011, with a selection of National Name Lists, 1600s – Present.