The following article is by my friend Bill Dollarhide, taken from his book, New York Censuses & Substitute Name Lists, 1613-2000 .

The following article is by my friend Bill Dollarhide, taken from his book, New York Censuses & Substitute Name Lists, 1613-2000 .

Prologue: This historical timeline for New York begins with the first discoveries and colonies in the area by the Dutch, then by the English; continuing through events leading up to New York’s admission as the 11th state of the Union, and New York at the time of the first census of the United States in 1790, as follows:

1497. Giovanni Caboto, an Italian sponsored by English King Henry VII, explored the Atlantic coast of North America. He claimed the area for the English King, who changed his name to John Cabot in honor of the event.

1524. Giovanni da Verrazano explored the Middle Atlantic region. An Italian hired by the King of France, he sailed past the present New Jersey coast, entered New York bay and saw the Hudson River, then headed north towards present Maine.

1558. Elizabeth I became Queen of England. The earliest explorations of North America took place during her 45-year reign, the Elizabethan Era, or “Golden Age.”

1606. Two joint stock companies were founded, both with royal charters issued by King James I for the purpose of establishing colonies in North America. The Virginia Company of London was given a land grant between Latitude 34° (Cape Fear) and Latitude 41° (Long Island Sound). The Virginia Company of Plymouth was founded with a similar charter, between Latitude 38° (Potomac River) and Latitude 45° (St. John River).

1607. May. Led by John Smith and his cousin, Bartholomew Gosnold, the London Company established the first permanent English settlement in North America – the Jamestown Colony.

1609. Frenchman Samuel de Champlain explored the upstate New York area, after dropping down from the St. Lawrence River. He claimed the region as part of New France, and managed to name several places after himself.

1609. Henry Hudson was an English sea captain sailing for the Dutch East India Company, with instructions to find a shorter route to China. His first northern voyage was blocked by ice floes, so he turned west, stopping at several places later identified (by Latitude-Longitude from his ships log) as the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Cape Cod, Chesapeake Bay, Delaware Bay, and the Hudson River. Unlike Champlain, Hudson did not give names to any of his stops, because he considered them all as reminders of his failure to find the Northwest Passage. The Hudson River seemed like the most likely candidate for the way to China, so Hudson navigated up the river as far as present Albany before giving up. His Dutch sponsors named the river for him upon his return.

1613. A Dutch trading post was set up on lower Manhattan Island. The Dutch discovered that a Swiss Army Knife would buy just about anything from the Indians.

1624. Fort Orange was established by the Dutch. It was the first permanent white settlement in the New York region, located on the Hudson River, just south of present-day Albany.

1626. Dutchman Peter Minuit purchased Manhattan Island from the Indians for about $24.00 worth of beads and baubles (according to my 1958 High School history book). The value of that real estate has since increased a little due to inflation and Donald Trump.

1652-1654. First Anglo-Dutch War. Under Lord Cromwell, the Commonwealth of England had become a larger naval force. The Dutch merchant ships were numerous and lucrative carriers of trade goods, but with far less firepower than the English warships. The resulting imbalance gave the edge to the English, who used it to consolidate their possessions in North America.

1664. The Dutch colony of New Netherland became controlled by the English following a naval blockade of Manhattan Island. Gov. Peter Stuyvesant surrendered following an “invasion” of about ten Red Coats, who had marched to Stuyvesant’s house on lower Manhattan. They knocked on the front door, and the Governor appeared and handed them his only weapon, a non-functioning dueling pistol. Stuyvesant then asked, “Are you fellows staying for lunch?” The English also took control of the New Jersey settlements from the Dutch with about the same amount of resistance. Soon after these glorious victories, King Charles II granted to his brother, James, the Duke of York, the following: “…the main land between the two rivers there, called or known by the several names of Conecticut or Hudsons river… and all the lands from the west side of Connecticut, to the east side of Delaware Bay.” Soon, the area called New Netherland was renamed New York.

1665-1667. Second Anglo-Dutch War. Restored to the throne in 1660, Charles II of England soon began a campaign to rid North America of Dutch colonies, replacing them with English colonies. Most of the battles were fought at sea. The rich merchant ships of the Dutch East India Company suffered the most.

1669. French nobleman Rene-Robert Cavelier (Sieur de La Salle), explored the Niagara region. He later floated down the entire length of the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers, claiming everything he saw for France.

1672-1674. Third Anglo-Dutch War. In 1672, bolstered by new warships, the Dutch East India Company took back New York, New Jersey, and Delaware from the English. By 1673, English King Charles II had lost the support of Parliament for continuing the wars against the Dutch. But England’s superior naval forces still managed to force the Dutch out of North America once again. The 1674 Treaty of Westminster ended hostilities between the English and Dutch and officially returned all Dutch colonies in America to the English. This ended the official Dutch presence in North America – but many of the Dutch settlements continued under English rule, particularly along the Hudson River of New York, and around Bergen in East Jersey.

1707. During the reign of Queen Anne, the United Kingdom of Great Britain was established after the Union with Scotland Act passed the English Parliament in 1706; and the Union with England Act passed the Parliament of Scotland in 1707. The English Colonies now became the British Colonies.

1763. Treaty of Paris. The French and Indian War ended. Great Britain gained control of all lands previously held by France east of the Mississippi River, which became the dividing line between British North America and New Spain. Soon after, King George III issued the “Proclamation Line of 1763,” as a way of rewarding the Indians who had helped Britain against the French. The proclamation established an Indian Reserve that stretched from the Appalachian Mountain Range to the Mississippi River — preventing the British colonists from migrating into their undeveloped western regions. The Proclamation was to become one of the “Intolerable Acts” that led to an American rebellion.

1765. New York City hosted a conference dealing with the Stamp Act, recently imposed on the British Colonies by the British Parliament. The conference was the first cooperative effort by the colonies to resist the “Intolerable Acts” imposed by the British.

1768. Treaty of Fort Stanwix. An adjustment to the Proclamation Line of 1763 took place in New York. The British government, led by Sir William Johnson, met with representatives of the Six Nations (the Iroquois) at Fort Stanwix (now Rome, NY). A new “Line of Property” was drawn, separating British Territory from Indian Territory. The new line extended the earlier proclamation line much further to the west. From Fort Stanwix, the division line ran to Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh) and down the Ohio River to the Tennessee River, then into present Kentucky and Tennessee. The Fort Stanwix treaty line effectively ceded present West Virginia and Kentucky to the British Colony of Virginia, and a sizable area of western New York and western Pennsylvania was opened for white settlement for the first time.

1776-1783. New York in the Revolutionary War. The 1777 Battle of Saratoga in New York was a major victory by the Americans; a decisive battle of the war that led the French to believe the Americans could win the war. The subsequent French alliance was to become the key to the American victory at the final battle of Yorktown in 1781. The 1783 Treaty of Paris ended the war, and the United States of America was officially recognized as an independent nation.

1788. Jul. 26. New York ratified the U.S. Constitution and became the 11th state. Albany was the state capital.

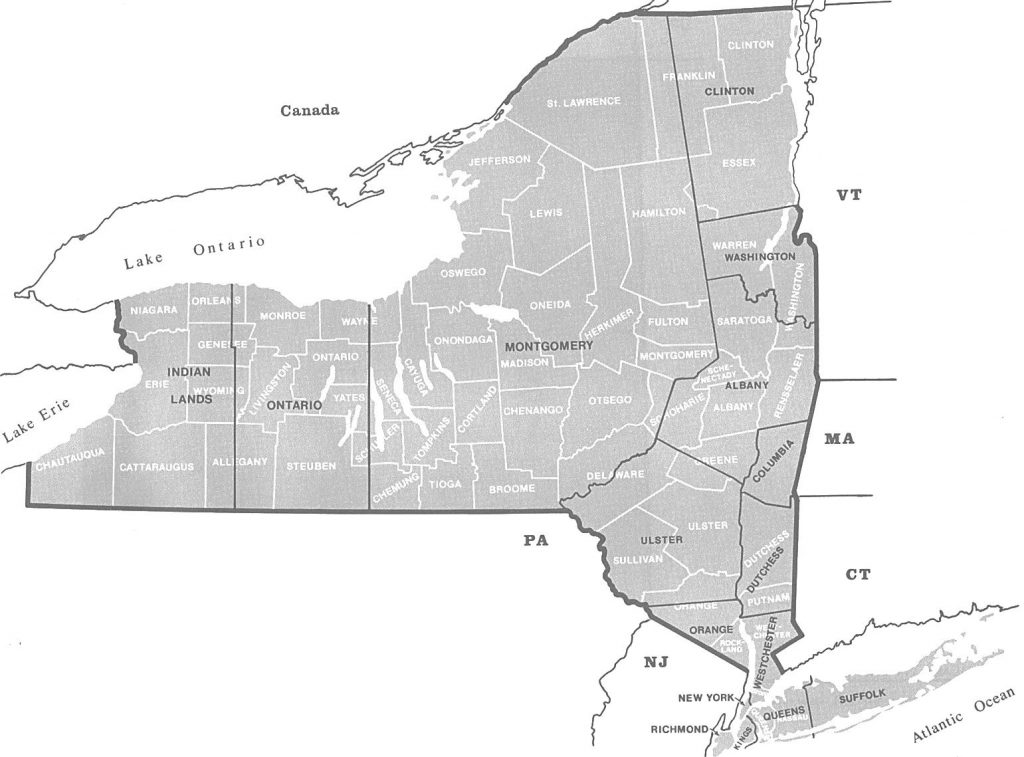

1790. Aug. Federal Census. The map above shows in black the 15 counties of New York at the time of the 1790 Federal Census. The current 62 counties of New York are shown in white. 1790 Map Source: Map Guide to the U.S. Federal Censuses, 1790-1920, page 236. NOTE: The area of western New York shown as “Indian Lands.” is shown in greater detail on the Royce Indian Cessions Maps (New York, Map 47).

About New York’s Censuses

NY State Censuses: The array of state census records for New York are more numerous and more complete than most other states. A few states have had more census years with territorial or state censuses, but none with the large populations of New York, and they are complete for virtually every one of the 62 counties of New York.

For the purpose of apportionment of the New York State Assembly, the legislature authorized censuses for 1795, 1801, 1807, 1814, and 1821, but none of these early “electoral censuses” included the names of inhabitants.

More formalized state censuses for New York began with an act in 1825, “An act to provide for taking future enumerations of the inhabitants of this state, and for procuring useful statistical tables.” Under that act, state censuses were taken in 1825, 1835, 1845, 1855, 1865 and 1875; then one in 1892, followed by 1905, 1915, and the last one in 1925. In 1930, the state began using the federal decennial census population figures for apportioning the State Assembly.

As part of the 1825 State Census Act, each New York county was charged with taking the state census for their area. And, the Office of the County Clerk was named as the final repository for the original manuscripts, with instructions to “carefully preserve the tables.” Two sets of the state census tables were recorded, the original set remained in the county, and a copy was sent to the state’s census office in Albany. Long before there was a NY State Archives, the NY State Library was the main repository for archival documents, including the state copies of the NY State Censuses.

The importance of the “carefully preserve” provision was dramatically fulfilled after a disastrous fire in the NY State Library in March 1911. The state copies of all state censuses, 1825-1905, were reduced to ashes. The extant census manuscripts for that period we read today on microfilm or online databases, came from the original county copies held in each of the 62 counties of New York. For 1915 and 1925, most county copies exist, as well as the state copies. For a look at the copies that exist for all 62 counties, refer to Table 1-NY State Censuses a full-page printable PDF file.

NY Federal Censuses: A spin-off benefit of the “carefully preserve” provision of the 1825 law was that the county clerks were also keepers of their original federal census schedules – there are more surviving county copies of federal censuses in New York than any other state. Beginning with 1790, the federal copies, those sent to Washington, DC, are complete for all NY counties through 1940, with the exception of the lost 1890 federal census for all states. But, only in New York are there 30 counties holding 105 county copies of original federal census schedules. (Michigan has ten county originals, the next highest number of any state). Each of the NY county original copies were microfilmed. Thus, the county originals can be compared with the federal copies for accuracy, i.e., missing names, different spellings, etc.

About Dollarhide’s First New York Censuses book

New York State Censuses & Substitutes , by William Dollarhide, publ. 2007, 250 pages, Item GPC1492. This book features an annotated bibliography of state censuses, census substitutes, and selected name lists in print, in microform, or online. The book includes unique county boundary maps, 1683-1915; and state census extraction forms, 1825-1925. The identification of state censuses and substitutes is for statewide lists, but also for each of New York’s 62 counties in great detail. An extensive description of the contents of this book is at the Family Roots Publishing product site for Item FR1492. After ten years in print, this book remains a staple at New York libraries and genealogical societies; and is recommended as a valuable desk reference by the prestigious New York Genealogical and Biographical Society.

New York State Censuses & Substitutes , by William Dollarhide, publ. 2007, 250 pages, Item GPC1492. This book features an annotated bibliography of state censuses, census substitutes, and selected name lists in print, in microform, or online. The book includes unique county boundary maps, 1683-1915; and state census extraction forms, 1825-1925. The identification of state censuses and substitutes is for statewide lists, but also for each of New York’s 62 counties in great detail. An extensive description of the contents of this book is at the Family Roots Publishing product site for Item FR1492. After ten years in print, this book remains a staple at New York libraries and genealogical societies; and is recommended as a valuable desk reference by the prestigious New York Genealogical and Biographical Society.

Further Reading:

New York Censuses & Substitute Name Lists, 1613-2000 (Printed book, with statewide name lists only), 2017, Softbound, 81 pages, Item FR0273.

New York Censuses & Substitute Name Lists, 1613-2000 (PDF eBook), 81 pages, Item FR0274.

Online New York Censuses & Substitutes: A Genealogists’ Insta-Guide™, 4 pages, laminated, 3-hole punched, Item FR0343.

Online New York Censuses & Substitutes: A Genealogists’ Insta-Guide™ (PDF version), 4 pages, Item FR0344.